Slow Progress in Japan’s LGBTQ Legislation

By Takuya Nishimura, Editorial Writer, The Hokkaido Shimbun

The views expressed by the author are his own and are not associated with The Hokkaido Shimbun

June 5, 2023. Special to Asia Policy Point.

For Japan’s ruling LDP and its government, G7 membership is considered precious for it gives Japan an advantage relative to other Asian nations. However, Japan is the only G7 member without any legislation prohibiting discrimination based on sexual orientation or self-recognition of gender identity, an embarrassment since Japan is the chair of the G7 this year. Although the LDP submitted a new non-discrimination bill to the Diet just before the opening of the G7 Hiroshima Summit, it remains unclear whether it will pass before the end of the current session on June 21. The rightwing powers in the Diet continue their efforts to derail the bill, regardless Japan’s status among developed countries.

The discussion over legislation for sexual minorities has been led mainly by Japan’s opposition parties. They submitted a bill to eliminate discrimination based on sexual orientation or self-recognition of gender identity to the Diet in 2016. The movement eventually included some of the LDP lawmakers. Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle reached an agreement on a multi-partisan draft of the new bill in 2021, but it was blocked by the conservative members of the LDP. Earlier this year, after a careless speech by Kishida that same sex marriage would entirely change Japanese society and much-criticized remarks by a staff member in the prime minister’s office on the legitimacy of discrimination against the LGBTQ community, the administration was pressured to do something to protect gender orientation and identification. Kishida further demanded that the LDP pass an LGBTQ law before the G7 summit.

Conservative lawmakers who had been blocking LGBTQ legislature have been annoyed by this pressure. In LDP internal meetings on the issue of sexual minorities, they worked hard to dilute expressions that promote understanding of sexual minorities in the multi-partisan agreement under consideration. The most controversial change was the mainline LDP’s willingness to replace the phrase “discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or self-recognition of gender identity shall not be tolerated” with the more ambiguous “no unfair discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is allowed.” The opposition parties objected strongly, saying the insertion of “unfair” is needless to say, because there is no such thing as fair discrimination.

Other parts of the legislation were watered down as well. All the phrases of “self-recognition of gender identity” in the multi-partisan draft were replaced with “gender identity” on the theory that self-recognition might be interpreted as self-profession. The LDP conservatives’ apparent concern was that someone might be sneaking into the wrong side of public restrooms or baths. The LDP also dropped the words “effort of school administrators [gakkou setchisha]" in education. The argument in the LDP was that teachers were too immature and unskilled in sex education to lecture about LGBTQ.

The LDP submitted a revised version of the bill to the Diet a few days before the Hiroshima Summit, receiving approval from its junior partner of the leading coalition, Komeito. Encouraged by the domestic legislative progress over gender recognition, Kishida, as the chairman of the G7 Summit, succeeded in organizing the leaders’ communiqué, including the section supporting a society where “all people can enjoy vibrant lives free from violence and discrimination independent of gender identity or expression or sexual orientation.”

After the summit, work on LGBTQ legislation bills became further complicated by the submission of several related bills. The Constitutional Democratic Party and the Japan Communist Party had already submitted a bill much the same as the multi-partisan draft, and the two parties did so on the same day that LDP submitted its own. The Japan Innovation Party (Ishin-no Kai) and the Democratic Party for the People submitted a third bill, which replaced the words of “gender identity” with “jendaa-aidentiti,” after the summit.

Not all the bills submitted to the Diet were discussed in either the Plenary or committees meetings. The Committee of Rules and Administration is chaired by an LDP lawmaker who selects the bills to be considered. Thus, a number of bills, mainly submitted by the opposition, are rejected even without discussion in every session. With the current Diet session ending June 21, time is running out to select and debate any bill selected.

While the political parties continue to struggle with LGBTQ legislation, the judicial branch is considering lawsuits brought in five Japanese cities by same-sex couples against the state. So far, three out of four courts have said that not allowing same-sex marriage is constitutionally problematic. At the end of May, the Nagoya Regional Court decided that provisions of Japan’s Civil Code or Family Register Act, which did not recognize same-sex marriage, were unconstitutional. The defect in the laws was that, the court said, “the same-sex couple of plaintiffs is excluded from the important personal benefit that is attached to a legal marriage.”

The court recognized the unconstitutionality of laws that do not recognize same-sex marriage, relying on Paragraph 2 of Article 24 of the constitution, which requires that all the laws be based on respect of individuals and the essential equality of both sexes in the choice of spouse. This is the first time for a court in Japan to recognize the unconstitutionality based on that clause. Although the Court did not comment on legislation under consideration in the Diet, the decision should be regarded as an expression of frustration with the slow progress in the legislative branch. This week, a court in Kyushu will issue a ruling on the fifth lawsuit.

UPDATE (6/16/23): After two years of discussion, the Diet passed a bill to promote understanding of sexual minorities. In the House of Councillors, the LDP, Komeito, Innovation Party, and the National Democratic Party (NDP) supported the bill. It was an amended version, actually a mixture of two bills, one submitted by the LDP and Komeito, and another by the Innovation and NDP. These four parties agreed on an amendment before the bill passed the House of Representatives on 13th. After an argument over the interpretation of “gender identity” in the Japanese language, the expression which would confusingly be recognized as allowing a man to enter a woman’s public bath, the four parties agreed on using the term of “jendaa aidentiti.” It also requires educational institutes to make efforts to achieve cooperation of families and local community before approving LGBTQ organizations. It is obvious that the law will be working as an obstruction to promote understanding of sexual minorities.

Fukuoka Regional Court ruled on June 8th that current laws related to marriage were in a “state of unconstitutionality,” because the plaintiffs, requiring the right for same-sex marriage, were suffering from the disadvantage of not being able to take advantage of the institution of marriage. Four out of five regional courts, including Fukuoka, Nagoya, Tokyo and Sapporo, decided that the laws were unconstitutional or in the state of unconstitutional on the lawsuits demanding recognition of the unconstitutionality of existing laws on same-sex marriage, urging the legislative branch to take further action. It is doubtful that the passed bill fulfills that requirement of the judicial branch.

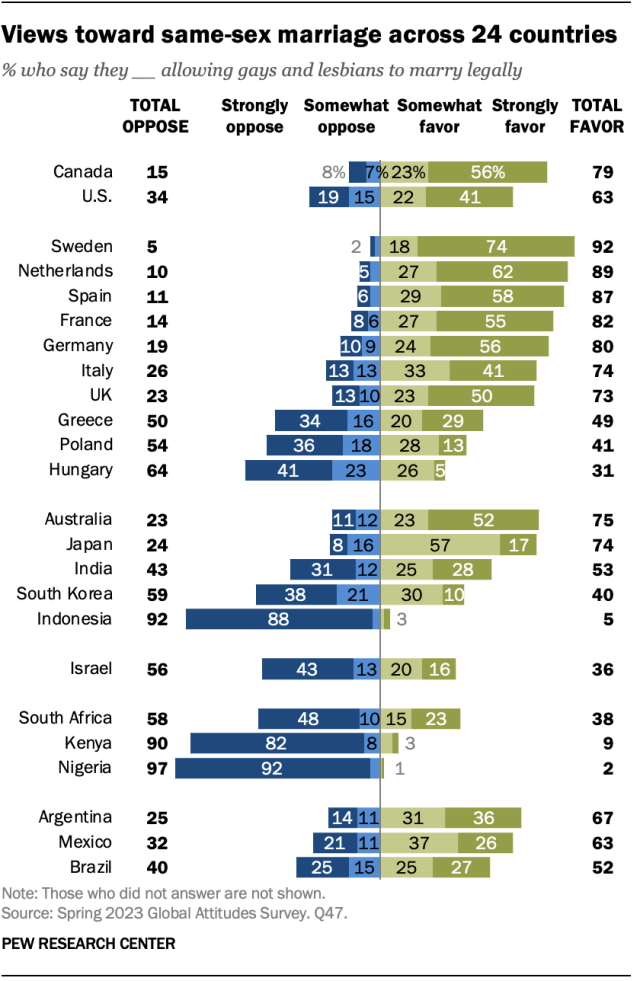

According to a Pew Research survey this spring of 24 countries, Japanese people have a 74% acceptance rate of same-sex marriage. This is not reflected in the Diet legislation.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Intelligent comments and additional information welcome. We are otherwise selective.